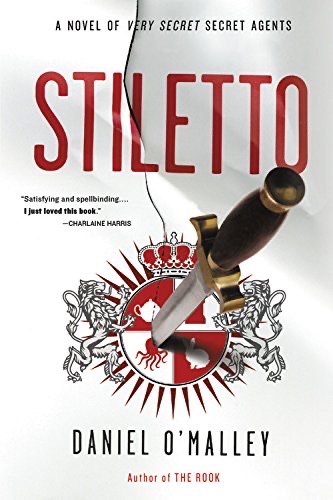

Stiletto

Myfanwy Thomas returns to clinch an alliance between two deadly rivals, and avert an epic – and slimy – supernatural war such as the world has never known.

After years of enmity and bloodshed, two secret organisations with otherworldly abilities must merge, and there is only one person with the fearsome powers – and bureaucratic finesse – to get the job done.

Rook Myfanwy Thomas must broker a deal between deadly rivals the Checquy – a centuries-old covert British organization that protects society from supernatural threats; and the Grafters – a centuries-old supernatural threat.

But as bizarre attacks sweep London, threatening to sabotage negotiations, old hatreds flare. Only Myfanwy and two women who detest each other can seek out the culprits before they trigger a devastating otherworldly war.

When I originally wrote The Rook, it was not with an eye towards writing more about the Checquy after the book was done. I thought the story of Myfanwy Thomas had come to a good ending and, as a bonus, two unimaginably powerful organizations that had despised each other for centuries were going to merge into a single force for good. We could assume that this would usher in a new age of cooperation and supernatural security, at least in the British Isles.

But, as the old saying goes, “You don’t spend years imagining a fictitious supernatural Government agency, and then just forget about it overnight.”

Almost immediately, I started thinking about what would happen next. The Checquy and the Grafters hated each other, and had done so for centuries. Each organisation brought up their operatives to loathe the memory of the other. They were each other’s worst nightmare.

Plus, by that time, I’d had the opportunity to witness and learn a bit more about institutional change in the real world. Something as simple as a new head of organization can mean a lot of ruffled feathers. The merging of Government offices – even ones that haven’t waged supernatural war on each other – can result in cultural clash, and a lot of tension. And I was writing about powerful bodies whose hatred was practically religious. The more I thought about it, the more naïve it seemed to assume that the joining of the Graters and the Checquy would go smoothly. There were centuries of built-up fear and loathing, and no one was going to trust anyone fully. There was every chance this merger would instead break out into supernatural war.

This was something I wanted to explore.

I knew that I was going to need new point-of-view characters. In The Rook, Myfanwy finds herself dropped into an institution, she has to head up that institution, but she lacks any of the institutional memories, prejudices or assumptions. It’s one of the things that make her so effective. But to examine the hostility between the Checquy and the Grafters, I was going to have to get inside the minds of people who really felt that hostility, on both sides.

All throughout The Rook, the Grafters were shown as faceless (in some cases, literally) horror-scientists who undertook creepy, stomach-turning surgeries and processes to alter the human body. How could I portray them as reasonable people, who were worthy of merging with the magically powered Checquy?

So, two new characters to throw into the mix: First, Odette Leliefeld, the young scion of the Grafters who has been sent as part of diplomatic party to the heart of the Checquy. And second, Pawn Felicity Clements, the Checquy soldier who is assigned to act as Odette’s bodyguard and, if the order is given, as her executioner. Both have been brought up since childhood in their respective groups, fully indoctrinated, with a lifetime of stories about how dreadful and unnatural the other is. Both are important in their respective organizations, but neither is nearly as powerful or prominent as Rook Myfanwy Thomas, which meant I’d get to explore the perspective of troops on the ground.

Plus, you wouldn’t believe how difficult it was in The Rook to keep justifying a high-ranking Government employee being flung into a situation of danger and action. People will accept someone with the power to turn into a bison or who can extrude unbreakable filaments from their teeth, but the prospect of an executive constantly going out in the field? Simply too implausible.

And so I wrote Stiletto.